07-1 – The history of the original

The giant Sequoias trees are one of the wonders of nature’s world. To grow to be that impressive required

constant vigilance towards the goal with the right conditions over a long time. They require strong, deep

roots…and a little luck.

Similarly, without a doubt, to the readers of the Shelby American Registry, the Ford

MKIV is one of the wonders of the automotive world. To be that impressive, the car required constant vigilance towards the goal with just the right conditions over a long time. It required strong, deep roots, a little luck and to a Shelby fan, it has all the majesty of giant SequoiaIt needed strong, deep roots, a little luck, and for a Shelby fan, it has all the majesty of a giant sequoia.

Here’s some background information:

The MKIV is impressive – it was the world’s first race car to use a lightweight honeycomb chassis (basically a supersonic fighter on wheels), and was developed through the combined efforts of several talented engineers.

The father of the GT40, Roy Lunn, realized during the 1964 Nassau races that more horsepower would be needed to stay ahead of the rapidly evolving competition. He suggested using the 427 cubic inch “big block” engine to accomplish this goal, resulting in the MKIV powertrain.

The roots of the MKIV chassis concept can be traced back to a conversation between Ford

engineer Charles “Chuck” Mountain and the then development driver Bruce McLaren in England at the end of 1964. The topic was how to make a chassis lighter yet stiff enough to cope with the large and relatively heavy 7-liter engine.

Chuck was one of three Ford USA engineers (the others were Len Bailey and Ron Martin) who had spent the previous six months helping Roy Lunn set up the Ford Advanced Vehicle (FAV) design office in Slough, England, where they worked with Eric Broadly to design the GT40 MKI.

By the end of 1964, the GT40 program was at a critical point of change: FAV had made a firm commitment to

focus on production of the MKI cars; Shelby was given control of the GT40 racing program, and Roy Lunn and Chuck Mountain left England to start another “skunk works” shop called Kar Kraft Inc. closer to FoMoCo headquarters in Dearborn, Michigan.

Kar Kraft was a private company with a single customer – Ford – and worked under the direction of Roy Lunn of Ford Advance Konzeptes.

Kar Kraft utilized the talents of the Ford Motor Company, with Ford engineers working “side jobs” in the nearby Ford engineering offices after hours. The first task was to work on a concept that included a 7-liter engine and a newly developed transmission that could handle the torque. In the spring of 1965, the drivetrain was installed in a standard GT40 “Mule” chassis (GT40P-106) with the sole purpose of testing the drivetrain for the upcoming 1966 GT40.

The genesis of what would later be known as the MKII is covered elsewhere, but the fact that the 7-liter engine had potential was clear to all. It was simply insufficient preparation time that prevented the MKII from winning Le Mans in 1965.

After the 1965 Le Mans race (the second year in a row that the Ford GT40 failed to finish), Special Vehicle Operations (SVA, the division at Ford responsible for all racing programs) held a “Come to Jesus” session.

It was concluded that the best approach to winning in 1966 was to “divide and conquer”. Internally, SVA created a new position called “Manager of GT Development”. This position was filled by Homer Perry who, as the title suggests, was responsible for managing the development of the GT40 program.

Additional preparation and course resources were provided in the form of Holman and Moody, as well as Alan Mann, who were also brought on board. The course was set: The focus would be on the MKII for 1966, while Advance Vehicles would develop a new, lighter and faster replacement as a reserve for 1966 and eventually as a replacement for the MKII when it became obsolete. The all-new car would comply with article “J” of the FIA regulations and be appropriately named the “J-Car”.

J-Car concept drawing, personalized by Roy Lunn

The objectives of the “J” car project were to develop a more aerodynamic body shape around the 7-liter powertrain and a new lightweight chassis to compensate for the additional weight of the new engine and transmission.

Chuck Mountain never forgot his conversation with Bruce McLaren a few months earlier, and neither did Bruce. In the fall of 1965, Bruce McLaren was experimenting with an aluminum GT40-MKI chassis and a lightweight 427 engine for competition in the newly formed “Can-Am” series (see GT40P 110 chassis history). At the same time, Chuck was researching different technologies and came across the Brunswick Corporation, which manufactured honeycomb dashboards for fighter jets.

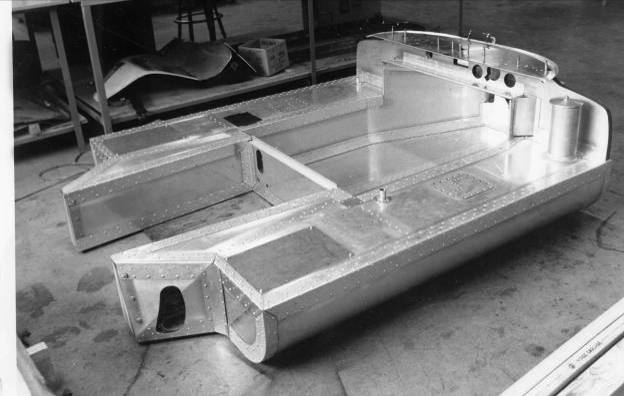

Naked honeycomb MKIV chassis

The other talented engineer in the history of the J-Car is Ed Hull. Ed was given the task of being the concept engineer for the J-Car. Ed had been on the Advance Concept team since the days of the Mustang I, and in his spare time at home had developed the layout for the T-44 manual transmission used in the seven-liter cars, as he believed that automatic transmissions were unreliable (which turned out to be true).

Ed put the J-Car concept on paper (still using a pencil and ruler at the time). The package was then finalized at Ford Styling, where Gene Bordinat led the design team to produce the clay model and fiberglass molds.

By the spring of 1966, the J-1 was completed in time for the Le Mans test days. By this time, however, Homer Perry had done his job well and pushed the development of the MKII so far that there was little resistance within Ford to change course at such a late stage. The decision had been made – it would be the MKII that would go down in the history books with 1st, 2nd and 3rd places at Le Mans in 1966.

After the victory, most of SVA’s exhausted executives wanted to “rest on their laurels”, but Henry Ford II decreed that Ford should win Le Mans again in 1967, but with an “all-American” racing car. This quickly changed everyone’s opinion.

Development of the J-Car continued in the summer of 1966, but suffered a tragic setback with the death of Ken Miles at the wheel of the J-2 in August 1966. It was not until the spring of 1967 that Chuck Mountain, together with Phil Remington (chief engineer at Shelby American) and Homer Perry, redesigned the J-Car in the wind tunnel and gave it the now famous MKIV shape.

The J-Car was converted into the MKIV in Ford’s wind tunnel.

The first outing for the redesigned car was at Sebring in 1967, where Mario Andretti and Bruce McLaren (now realizing his dream that a lightweight would be competitive) won a thrilling 12-hour race against the Chaparral and an MKIIB driven by AJ Foyt.

Ferrari wasn’t there, however, so there were still valid concerns. To further the effort, the J-3 was used in the rainy test days at Le Mans to “make the final set-up”, but there was still no good competitive comparison with Ferrari.

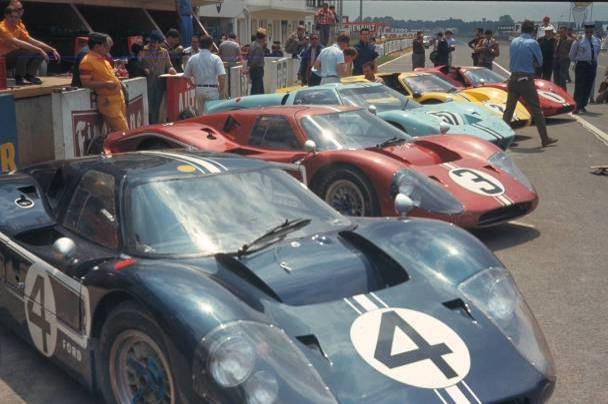

At Le Mans 1967, three MKIIBs and four new MKIVs lined up for the famous Le Mans start.

The starting grid of Le Mans 1967

The result is history:

For the first time, a car designed, delivered and maintained in America won the 24 Hours of Le Mans. The J-5 chassis in its red livery and with its round emblem (on which the number 1 was intuitively emblazoned) easily defeated the competition with Dan Gurney and A.J. Foyt at the wheel.

J-5 not only survived the grueling, accident-prone race and took first place in the overall standings, but also won the Index of Performance Award, the prize awarded by the French FIA organization for the most fuel-efficient car.

The MKIV was so superior in its double victory that the FIA simply gave up … The rules were rewritten so that these ground-based jet fighters became illegal.

The change was necessary so that the rest of the automotive world could compete among themselves at a lower but more balanced level. The GT program, which had taken so much time and energy to develop up to this point, was discontinued.

Ford was thus immediately eliminated from direct competition in sports car racing – and gave up while it was in the lead.

Two winners!

Enough history

This story is about what we call the “Kar-Kraft MKIV” (for lack of a better title, but that can’t hide the fact that the project is the result of a truly impressive group of Ford enthusiasts and has been many years in the planning). Fast forward from 1967 to 1989 …

At the time, the thought of seeing, touching, driving and steering the MKIV was the stuff of long daydreams. All 12 original chassis existed in one form or another (10 as complete cars and the first two as a handful of parts of each).

Because so few original cars were built, they would fall under the Endangered Species Act. These cars are so valuable and so coveted by their owners that they are rarely let out of their protective cages. Most enthusiasts are lucky if they’ve ever seen one, and have to make do with a photo or video.

You can find the continuation of this story in Part 2 – The Kar-Kraft MK IV.